D&D: Quiet Railroading

This post was drafted in October 2018.

As I’ve been slowly pushing into becoming a public and professional Games Master, more and more people have been asking me about how I do what I do. This has been useful for me, as after a decade and a half, I do a lot of these things without thinking. Slowing down and examining exactly how I create (or co-create) the games I do has been an interesting exercise in introspection. Now, like anyone with a blog, I want to talk about it.

I was recently asked how I deal with quietly railroading my players, while still giving the impression that literally anything could happen. Railroading, if you’re unsure, is forcing your players down a certain route. It usually happens when a GM hasn’t prepared enough material to be comfortable, or when their heart is set on a particular story told with particular beats.

My immediate reaction is that I don’t railroad. The major advantage – and selling point – of a table-top RPG is the capacity for improvisation. As huge and as open as games like The Witcher 3 are, their developers are inherently limited by having to code everything, and call a halt to the writing at some point. To really feel the impact of some of the choices that you’re called to make as an adventurer, you need to see them have an effect on the world. There have to be consequences, good and/or bad. When you’re coding a video game, you’re always going to be limited to pulling together these effects and stopping them at some point.* Tabletop RPGs have the advantage of being able to be changed in real time and in response to the player’s actions. This can be as broad as the death of a whole village or as detailed as scorched stones or fashion trends. I don’t want to think of myself as railroading because I want to afford my players this experience.

What people are really asking when they ask how I railroad is “how do you keep your plot on track?” This is something I can do. In exactly the way a video-game might.

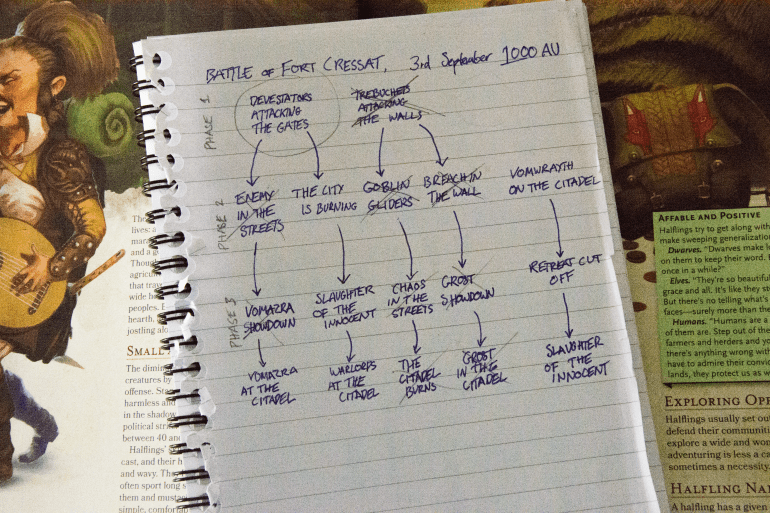

My players were in a besieged city that was woefully under-prepared and depleted. The party was the best hope for the people and they were determined that they would save as many people as possible. I wanted the battle to feel large and difficult. I was looking for a Minas Tirith feel – overwhelming, hopeless, too much to do. But I also wanted to give the players choices. I wanted to get them involved in the strategy of the defence. So what I created was the flowchart pictured above. The idea was that there would always be at least more than one thing than the party could handle going on. They needed to triage the problems and deal with what they thought was important. They would cut off that danger, but the other two or three would progress. It was a good session that left the players snatching a Pyrrhic victory from the jaws of total defeat.

When I was asked about how I railroad, this is what occurred to me – this is how I do it. Provide obvious choices and prepare outcomes for each of them. In the context of TTRPGs, make sure the choices require the whole party to deal with them, to discourage any party splitting to try and “game” your system. Then have ramifications later on, to make the decisions have weight. In this way, you can invisibly plan to keep the plot moving and on track – the plot here being the siege.

I also follow the flowchart type of system with the main plots of my stories. If the villain is serious about getting anything done, he might have lieutenants to delegate tasks to. If the party deals with one of the lieutenant’s plans, then advance the other’s plan down the flowchart, or timeline. Now the villain has ‘resource a’ but not ‘resource b’ – we can plan out their next step. If they really need ‘resource b’, how are they going to double down on getting it, now that they know that the heroes are defending it. If they feel they can move on to ‘plan c’ with ‘resource a’ alone, then perhaps they do that instead. The trick here is remembering that the villain knows what they’re doing.

In the campaign mentioned above, my party are aware of multiple ‘main villains’ at any one time. Every time they neglect frustrating one in favour of chasing another, the others advance, become more powerful, become more of a growing problem. There are so many benefits to this. Firstly, they players get to feel real elements of choice without ever coming off of material you’ve planned. Secondly, those choices only become more and more difficult. Thirdly, there is a natural escalation to the threats as the villains grow in power, which is great for a system with rigid levelling like D&D.

Last, I find it doesn’t actually require any more planning than I would already do. Instead of a linear plot where stopping Grunt R leads to knowledge of Lieutenant S and then Right-Hand Person T, before the big villain, you have R, S and T all available to tackle at once. They are all problems and they all need to be dealt with but the players get to have a crunchy decision about who is more urgent, and they emergently write your plot for you.

*That is, until there’s a massive and scary step forward in tech.