D&D: Starting Small

As I’ve been slowly pushing into becoming a public and professional Games Master, more and more people have been asking me about how I do what I do. This has been useful for me, as after a decade and a half, I do a lot of these things without thinking. Slowing down and examining exactly how I create (or co-create) the games I do has been an interesting exercise in introspection. Now, like anyone with a blog, I want to talk about it.

“can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?”

This is from the middle of the Prologue to Shakespeare’s Henry V. In it, Shakespeare asks his audience for forgiveness that he’s not going to be able to impart an entire two countries going to war onto his stage. But that’s the story he needs to tell, and that’s what happens in it, so he asks the audience, either kindly or tongue firmly in cheek, to just imagine it.

One piece of advice I hear a lot of people give with world-building is to start small. This is, of course, good advice for building anything. Great projects come together piece by piece, and grand designs can intimidate and put people off. I often tease my players with “ooooh, wait until you see what I have planned!”, but I try to never sell them on a crazy grand narrative. We snowball into these things. I’ve just counted, and one of my current games has 168 non-player characters, alive or dead, that have been involved at one point or another. The players met them one at a time.

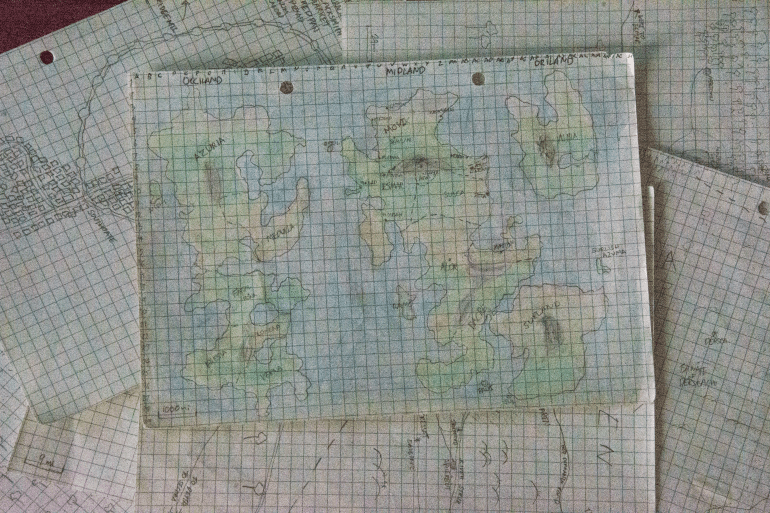

However, I do think that this advice – “start small” – can be very misleading when it comes to world-building. I started writing the aforementioned game by sketching out a map of four continents, on squared paper with a scale of 333 miles per half-centimetre edge. While I was doing this my flatmate at the time, who is also a GM, warned me that I shouldn’t be doing it that way. He told me that I ought to be starting with a single village or hamlet, or I’d get lost. I politely told him that I knew what I was doing – besides, I was having fun and that’s the point. But why did I have this gut reaction? Why did I know that the world map was where I needed to start.

[Spoiler Alert, I guess, if you’re one of my players]

I think it’s because of the story I wanted to tell. The idea I had was of nations desperately trying to pull themselves out of the jaws of a World War. I’d been learning a lot at the time about World War I for my day job, and I ideally wanted my players to be present at the fall of the first domino. I wanted them to see the death of my world’s Franz Ferdinand, and I wanted to see if they could stop the cataclysm, and in the midst of all that is when the Big Bad Evil Guy would turn up. This wasn’t a story about a megalomaniac necromancer holding the world to ransom, this was a story of good intentions paving the way to hell itself.

So in light of this, and I think I would change the advice from “start small” to “tell the story in front of you”. When you’re sat in a living room with your mates and a muse of fire, things I needed the grand world map because I needed to be able to reference countries from the beginning, to make the players aware of the world stage.

The first thing you should do with building a world of your own is to plot the story you want to tell in it. Beats, scenes and acts are more important than set dressing. Being aware of where your stories are going allows world-building to feel intevitable. Instead of saying “Ah, here’s where the GM’s story is trying to lead us,” you’ll hear your players cry “Of course The Kingdom to the South attacked us! They’ve been after us for decades!”

Your story is almost always going to start small, especially your first story. You’re in some village with no recourse but to throw itself on the help of adventurers. I did that with this campaign too. After I had created my plot and world map, I zoomed right in. I needed to get the players up to a decent level before I threw them at my main plot, so I didn’t have to pull punches with the encounters I wanted to run. However, knowing where the plot was going allowed me to start sprinkling the clues from the very beginning. The whole reason the village needed to hire adventurers was that the Baron of the Fort was away in troubling meetings with the Marquess and his steward wasn’t handling things very well and blah blah blah. The small stuff tends to build itself after a while.

The important thing, and the thing you see in all the published modules that Wizards of the Coast have released for 5th edition D&D, is building your narrative into the essence of the world so that it feels like the most natural thing for the players to pursue. The presentation also matters, of course. If you look over the screen with a coy enigma and say “but the evil drow live under the mountains, you shouldn’t go there…” as your hook, then your players are more likely to feel like it’s contrived. If you’ve dropped the drow into conversation an hour ago, and the players have had time to process the idea, then it comes as no surprise when their expedition leads them into a grand arc of dark elf nastiness. It makes sense.

So the advice is this: plot your story before you dress your set. Don’t forget that the fantasy map that started them all, in The Hobbit, was a prop not a tool. It wasn’t a crutch for readers, it was an object involved in the story. Bilbo had that map, that’s why it’s there. The story was about that map. If you don’t need a map, don’t worry about one.

Tell the story that’s in front of you, and world-build for that story.